Story by Edwin Manuel Garcia

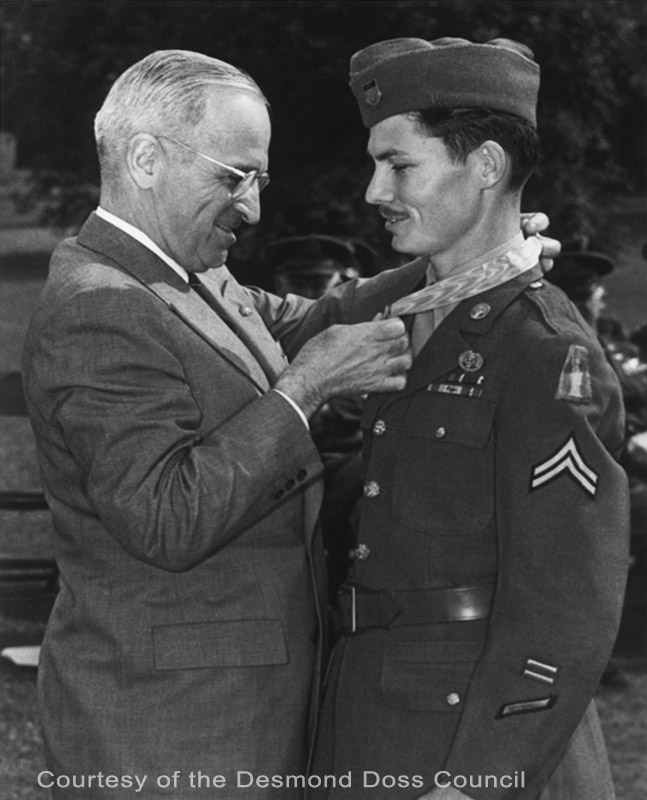

Before he saved dozens of wounded soldiers on the front lines during World War II, which earned him a Medal of Honor, Seventh-day Adventist combat medic Desmond Doss (pictured below with President Harry Truman) was called a misfit for refusing to carry a weapon, and commanders ostracized him for observing the Sabbath.

Life wasn’t easy for Doss and other Adventists in the U.S. armed forces.

Life wasn’t easy for Doss and other Adventists in the U.S. armed forces.

But 70 years later, the military has become a more welcoming institution for Adventists, according to active and retired military personnel within the Columbia Union. This is a marked change from when Doss enlisted as a noncombatant with conscientious objector status.

Several servicemen and servicewomen recently spoke in detail about their experiences serving God and country, and how they personally dealt with any tug of wars between the two.

Religious Tolerance

“The military today is much more tolerant toward religion,” observes Major Andre Ascalon, a chaplain for the New Jersey National Guard, and pastor of New Jersey Conference’s Newark and Elizabeth Seventh-day Adventist churches. “There’s no reason for any soldier today to be able to say, ‘I cannot go to church, or worship my God.’”

As a young soldier in the 1980s, in Washington, D.C., Europe and Asia, Ascalon knew that keeping the faith in a secular environment would be a challenge, but he vowed to remain true to his religious beliefs.

That meant waking up at 3 a.m. for his daily devotional and disassociating from the rowdy crowd. “When I’m in a barracks as a single soldier and Friday comes, it’s party time; they’re blaring their music and I’m listening to my Christian music,” he said. “It took an enormous amount of discipline for me to [stay focused].”

That meant waking up at 3 a.m. for his daily devotional and disassociating from the rowdy crowd. “When I’m in a barracks as a single soldier and Friday comes, it’s party time; they’re blaring their music and I’m listening to my Christian music,” he said. “It took an enormous amount of discipline for me to [stay focused].”

A vegetarian, Ascalon didn’t always find healthy food choices in the mess hall. The military provided him extra money so he could purchase sources of

protein elsewhere.

Ascalon stood out from the rest, even before becoming a chaplain.

“I remember one particular day: I was working in an office and somebody said, ‘Ascalon, you don’t drink, you don’t smoke, you don’t chase women, you don’t go to clubs—what do you do?’”

His response: “I’m a Seventh-day Adventist.”

Soldiers respected him. They trusted him with their problems. “People were drawn to me,” said Ascalon.

“The person who is faithful to their religious beliefs and convictions, makes a better soldier in the long run. If a person is authentic, and espouses moral values, and is true to those values, then quite naturally that person is going to be a better soldier and better employee because they have core principles that they live by,” Ascalon said. “They believe in something, they stand for something.”

A Test of Faith

Janet Lomax, an active duty Naval officer currently stationed in Virginia, joined the military 27 years ago, motivated to save money for college.

Her first test of faith occurred on her second tour while assigned to the Naval Consolidated Brig in Miramar, Calif., when she had to tell her supervisor that her duty got in the way of Sabbath.

“One of the respons ibilities we had as duty officers was to do inspections of the cells and ensure that we did random checks. I saw one time that my name was on for the Sabbath,” Lomax recalled. “I asked to not have that duty and my boss said it was something we had to do in the military. He said that he could not give me special treatment, and that I should ask God or my priest for leniency.”

ibilities we had as duty officers was to do inspections of the cells and ensure that we did random checks. I saw one time that my name was on for the Sabbath,” Lomax recalled. “I asked to not have that duty and my boss said it was something we had to do in the military. He said that he could not give me special treatment, and that I should ask God or my priest for leniency.”

Instead, however, Lomax asked colleagues to trade shifts with her.

“Most people are supportive because they will either swap duty with someone else, or make up the work sometime; there are other times when that’s not possible because you’re the only person who has specific requirements or because the supervisor may not agree with how Sabbath is kept,” she explained. In one instance she explained her Sabbath situation to a chaplain and the chaplain told her boss about the importance of keeping the day holy.

Lomax, a captain who as born and raised Seventh-day Adventist, has had a positive experience in keeping her faith.

“What I love about being Adventist is that no matter where you go in the world, Sabbath School is the same. You get together with like-minded people, and it doesn’t make a difference what language or what area you’re in,” she said. “Within the body of Christ, you’ll always find someone willing to invite you home as a visitor for a meal or another activity.”

Makeshift Chapel

Patrick Reynolds, who enjoyed a fulfilling career in Navy submarines, grew up Southern Baptist but converted to Adventism seven years after getting married, thanks to the patient and faithful dedication of his wife to the Adventist message, and evangelistic meetings in Chesapeake, Va.

As a new Adventist, Reynolds (pictured below with son, Christopher,) was excited to share the message of the gospel during three-month deployments. He approached his captain: “Would it be possible for me to start worship services on the submarine?”

“Sure,” the captain said, “As long as you can also hold services on Sundays for other churchgoers.”

Reynolds created a makeshift chapel in the officers’ wardroom. He decorated the room with a cross he obtained from the chaplain on the naval base. Reynolds printed out the Sabbath School study guide and delivered a mini sermonette on weekends.

Reynolds created a makeshift chapel in the officers’ wardroom. He decorated the room with a cross he obtained from the chaplain on the naval base. Reynolds printed out the Sabbath School study guide and delivered a mini sermonette on weekends.

Attendance fluctuated between eight and 12 on the average. The entire submarine crew included 135 sailors.

After 20 years in the military, and three years on the last submarine, Reynolds decided he wanted to retire and attend the Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary in Berrien Springs, Mich. But he encountered resistance from his superiors. “We can’t let you go,” they said. “The Cold War is still around; can you stay 30 years?”

Reynolds then put his retirement request in God’s hands. He prayed, “OK, Lord, if you really want me to retire, you’ll let me out.” A dozen other submarine chiefs also put in their retirement papers, but only Reynolds’ was approved.

Now a district pastor on Maryland’s Eastern Shore, Reynolds is grateful for his military experience. “Working with multiple churches, you have to be very organized and very disciplined because you have to train your elders to do things when you’re not around, so the organizational skills I developed in the military are very helpful in running a multiple church district.”

Meanwhile, Reynolds’ son, Christopher, has joined the U.S. Air Force and is planning to start worship services where he is stationed.

Dealing With PTSD

Craig Johnson, who spent 26 years in the U.S. Army, including three tours in Iraq, sometimes finds himself combatting myths about the military, especially in relation to how much friendlier it has become to Adventists.

By the time he retired five years ago, from an assignment in logistics, the military had made significant strides in improving its menu in the mess halls by promoting healthful meals. “They are investing in you, so the longer they have you healthy, that’s part of their investment.” Nowadays, he said, soldiers can take to the field with MREs, or Meals Ready to Eat, which include vegetarian and kosher options.

The issue of Sabbath duty, and bearing arms, he said, is not as anti-Adventist as some people make them out to be.

Throughout his entire career, Johnson recalls having to work on Sabbath duty fewer than 10 times. “When I’m on duty, I’m with someone, and there’s fellowship,” Johnson said, recalling how he witnessed to a Mormon soldier.

“I don’t know where some get the idea that having duty on the Sabbath is a bad thing—it’s like having a dean on duty at the academy, having someone on duty there that’s accountable.”

Despite a satisfying career, Johnson, who works at Pennsylvania Conference’s Blue Mountain Academy and volunteers at nearby Blue Mountain Elementary School, also experienced a dark side of the military—he suffers from Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD).

The academy job, he says, is good therapy because he’s involved with a program that takes students to sing at nursing homes. “This has really, really helped me because I get to be with people that are lonely. Part of PTSD is that you can have 20 people around you but you’re lonely.” He says he can relate to the convalescent home residents, where his goal is to get them to smile by singing gospel songs such as, “Peace in the Valley.”

Influence for Good

Fleurette “Flo” Etienne, a reserve officer in the U.S. Navy who is active at Potomac Conference’s Cornerstone church in Aldie, Va., said keeping the faith in the military is similar to keeping the faith in civilian workplaces; in both situations you get a chance to influence and be influenced. “You select your friends no matter where you are, and people accept you for who you are,” she says.

Etienne, a nurse, enjoys comforting her patients at her job at a Veterans Health Administration hospital by offering to pray with them. “In uniform, or out of uniform, people have challenges.”

Serving God and Country

There are an estimated 6,000 Adventists serving in active and reserve components of the U.S. military.

“Adventists have an outstanding history of service to our nation in various capacities,” said Washington Johnson (pictured above with United States Navy sailors), assistant director at Adventist Chaplaincy Ministries (ACM) for the North American Division (NAD).

And, he said, the military is a “microcosm of society.” Some individuals, just as in civilian life, wrestle with personal decisions regarding faith, including Sabbath observance. “As a United States Navy Reserve Chaplain,” he explains, “I always share with Adventists encountering a Sabbath issue the importance of prayerfully going through the proper chain of command in requesting a Sabbath accommodation and not to act independently because their action, however sincere, can affect how Adventists are viewed in the military.”

Part of the ACM’s role is to assist and support Adventist military members and help prepare pastors’ transitions into chaplain roles in prisons, hospitals, educational campuses and the military.

Although most Adventists who were drafted in previous wars opted for the status of noncombatants, which is no longer allowed, the military continues to become more accommodating to more closely match the beliefs of church members, as well as worshippers of other faiths such as Islam and Judaism, said Paul Anderson, the NAD’s ACM director.

The military is becoming more accepting of Adventists, Anderson said, because “we have had leadership through the years that was better prepared to appreciate diversity,” not just in the complexions of soldiers, sailors, airmen and marines.

The military is becoming more accepting of Adventists, Anderson said, because “we have had leadership through the years that was better prepared to appreciate diversity,” not just in the complexions of soldiers, sailors, airmen and marines.

“As it relates to Sabbath observance, each of the military services have established policy allowing for ‘religious accommodation,’” Anderson said. Still, some service members will never be able to completely detach from their professional responsibilities for a full 24 hours, said Anderson, who served in the Navy for 20 years.

If the past is any indication, young Adventists will continue to enlist in the military, and some will turn to ACM for guidance.

The Adventist Church’s position on military service is reflected by a statement on noncombatancy that was voted in 1974. Yet, the church also recognizes the role of individual conscience, Anderson said. “ACM unflinchingly supports every Adventist who serves in the military.”

Anderson and his staff tell prospective recruits that if they are opposed to bearing arms they should not enlist or seek a commission in the military. If they do join, Anderson said, the Adventist member should dialogue with his or her supervisor at boot camp—and ensuing commands—to explain their faith.

“I think it’s incumbent upon the Adventists to be settled in their mind about what is good and acceptable service to the Lord and the church,” Anderson said.

Edwin Manuel Garcia writes from West Sacramento, California.